How are cultural institutions adapting and how are architects designing new cultural spaces for the future?

We talk about adaptability a lot in regard to design and the state of the world at present. We know that shifting on our axis is essential to moving forward in the face of challenging ecological, global times.

One such sector of culture that has been hugely effected by the past two years of events, are the cultural institutions that shape our society and bring together educational, informative and inspiring narratives, to safeguard our history and provide access to information in a very real, interactive way.

But, how are cultural institutions adapting and how are architects designing new cultural spaces in a way that will, not only benefit us in the future but remain as impressive monuments whilst being accessible for all?

Alan Maskin, Principal and Owner, Olson Kundig

Alan is a principal and owner of Olson Kundig, where he leads an interdisciplinary team of architects, designers, visual artists and researchers. For almost three decades, Maskin has pursued unconventional design challenges in public places. His built international portfolio includes museums, installations, exhibits, visitor-based destinations and urban park projects.

Alan Maskin, Olson Kundig

This past spring and summer, some of us began emerging. The unpredictable global contagion seemed to be getting, predictable. If one was vaccinated, boosted, avoided large indoor gatherings and stayed masked, there were decent odds that your test results would remain in the green zone.

It was a return to public culture, Alan thought. Alan went inside a movie theatre to see the new Wes Anderson film, French Dispatch. He sipped a negroni at an Italian restaurant. He returned to the gym, attended a museum opening, travelled for business meetings, and visited with friends indoors.

With the rapid spread of the latest variant, last week eight friends and clients – all vaccinated, most boosted, the kind of people who self-described as “highly cautious” – tested positive. In all instances the symptoms appeared to be relatively mild, but it felt like an abrupt return to the bunkers.

In the early spring of 2020, Olson Kundig entered a competition for a new student center at Rice University in Houston, Texas. The company was shortlisted to advance to the design stage with two other outstanding firms. In the light of the pandemic, the Rice jury decided the competition would continue virtually. The team had already dispersed, working remotely away from the studio.

Had this competition occurred before COVID, Alan was certain their design response would have been different. The company inverted the program: setting up a series of floating boxes and providing an almost equal number of indoor and outdoor “rooms,” under an enormous, energy-producing shade canopy. During an earlier campus visit, they had climbed an adjoining “campanile” tower, finding cooler breezes and lower temperatures above the tree line. That experience informed the vertical positioning of some of the outdoor spaces. The company lost the competition, but as is often the case, the ideas stay.

In truth, Alan has been interested in activating elevated outdoor spaces for many years. After designing three rooftop parks in Asia, the company created a research project called The Fifth Façade that explored this underutilized upper layer of cities. The company found historic examples of schools in Manhattan that used the rooftops as safe places for kids to play, to grow gardens for food, for observation. Olson Kundig drew an enormous mural of their own neighborhood in Seattle to imagine the potential of a publicly accessible top layer.

Shortly after, the company redesigned Seattle’s Space Needle – capitalizing on architectural “prospect” by transforming a rooftop observatory. They added 200% more glazing (which in their minds meant 200% more view), including the world’s first rotating glass floor.

The “outside” phenomenon heightened by the pandemic has also bolstered a strong interest in outdoor schools. There are a dozen programs in Seattle, nearly all created during the pandemic, where kids spend almost every minute of their schooldays outside – including in the rain – getting back into nature for long stretches of time. A STEM-based children’s campus Olson Kundig redesigned for the Bay Area Discovery Museum in Sausalito, California, has seen record attendance – largely because much of it is outdoors.

It rarely snows in Seattle, but just after Christmas, the city had a storm and bitter cold temperatures. On New Year’s Day Alan received two messages on Instagram. One included a video of the outdoor observation platform on the Space Needle, covered with snow. The other showed a group of his friends on New Year’s Eve, celebrating together – outside.

Emma Holt, Associate, Ben Adams Architects

Emma has extensive experience in the design of complex schemes within a range of sectors from residential, and hospitality, to culture. Emma worked on the award-winning Nobu hotel in Shoreditch, and recently, Graphite Square, a 300,000 sqft mixed-use project in London’s Vauxhall.

Emma Holt, Ben Adams Architects

Buildings for art and culture need to be functional and economic; housing organisational headquarters, archives or core operations whilst driving public engagement through beautiful, flexible spaces which allow for imaginative programming.

As a practice, Ben Adams Architects look to how cultural institutions shape the community, its surroundings, and how design not only respects heritage, but also looks to the future. It is incredibly important that design, as with any sector, allows for spaces to adapt with time, remaining relevant while providing access to information to all, that continually inspires and engages. The company has applied this thinking to their own cultural projects which include the British Film Institute, Phillips, and Hauser & Wirth.

Working with the BFI saw Ben Adams Architects working collaboratively with this institution, echoing its principles to promote and preserve filmmaking and television, learning, and accessibility. The relocation of the BFI library to London’s Southbank gave the BFI the opportunity to rethink its existing HQ at Stephen Street, and create a new vibrant, and welcoming space for film lovers to enjoy.

The tired 1960s building was transformed to reflect the BFI’s desire for more transparency, visibility and public engagement; improving facilities for its own members, connectivity with the street and access for the wider public. Here, the new foyer space was envisaged as a hotel lobby with a flexible ‘film set’ acting as a backdrop for people to converse. The building was stripped back to expose the existing concrete structure and high ceilings, and internal layout of the ground floor and café space feature glass partitions to give a more intimate, club-like feel. This is teamed with two basement screening rooms, meeting spaces, conference rooms, and a lounge that can be adapted for public events, as well as a new landscaped terrace area. The design interventions aim to foster creativity and improve the understanding and profile of British film-making, with a new informal space which encourages new ways of working with the organisation.

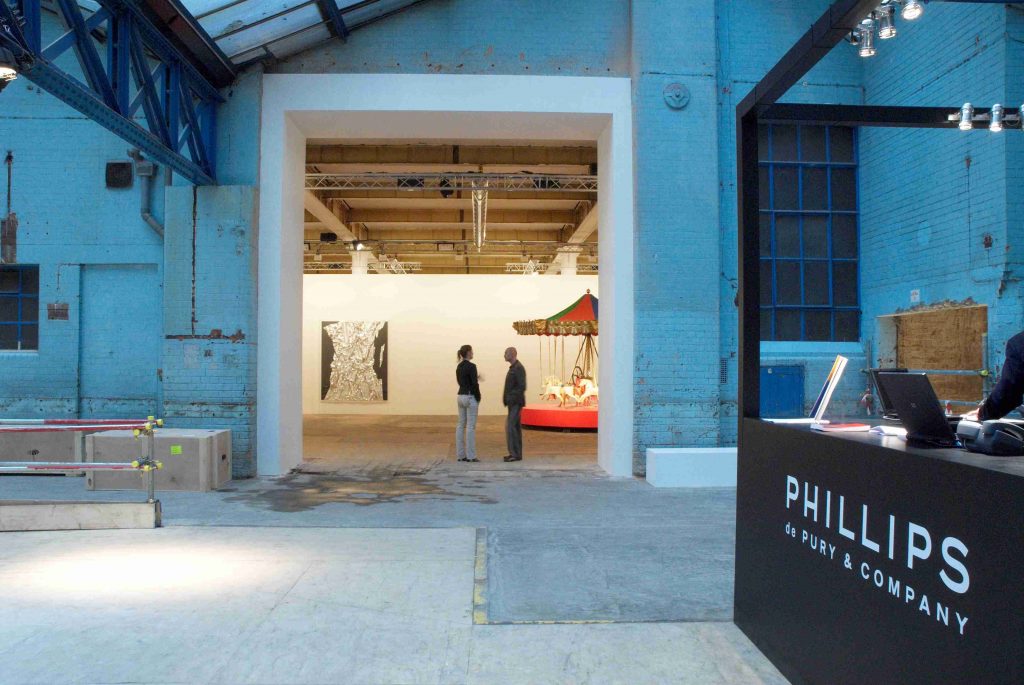

Similarly, Ben Adams Architects project for dynamic and forward-thinking auction house, Phillips embraced flexibility, and wanted a space that would harness the energy of the London art scene, that would allow for exhibitions, auctions, and private sales. Our retrofit of Howick Place, an old warehouse in Victoria, created free-flowing galleries and generous auction spaces, that not only allowed for a variety of configurations to suit a huge range of work, the space was welcoming and open to all.

The buildings industrial qualities were celebrated, and were used to contrasted with the pristine white walls that make up each gallery. Whilst work on Howick Place was underway, Ben Adams Architects also designed a temporary exhibition space in Bloomsbury; here they designed a series of raw interlinked galleries that weave together a series of basement rooms with varying floor levels and ceiling heights. This space is defined by a pleasing contrasts between lighting, concrete basement space, and traditional white walls of the modern art gallery.

For Hauser and Wirth expanding their offering with the opening of its 23 Savile Row outpost, with private galleries and support spaces within this prominent, yet discrete, corner site building. Ben Adams Architects designed two new exhibition spaces, the North Gallery and the South Gallery, as well as a new library, private offices, and an open plan reception area. Private clients come to Hauser & Wirth to discuss individual pieces of art, or whole collections, and the new floor creates an intimate space in which to meet dealers and collectors, and support the operations of the galleries below.

The world certainly feels like it has changed as we emerge from the pandemic and set our sights beyond Covid-19. As the world has changed, our cultural institutions have had to rethink how they address the environmental, health and economic impacts, to ensure that they remain accessible to all in the future. At Purcell, they work with some of the nation’s most recognizable cultural institutions and have insights into how the sector can address these changes. At the Royal Society of Sculptors [RSS], they are undertaking conservation works to the listed building Dora House to improve its overall condition. The works will ensure the building befits its use and function in supporting sculptors throughout their careers and in facilitating a wider appreciation of sculpture via active engagement with the public.

Louise Mark, Senior Architect, Purcell

Louise has been part of the Purcell team since 2015, with specialist expertise in delivering exciting but complex heritage projects such as at Fulham Palace and Battersea Power Station, through all RIBA work stages. Louise has prior experience of working within statutory authorities within the heritage sector, and works for clients across the private, charitable and public sector and is adept at working within high constrained budgets.

Louise Mark, Purcell

The world certainly feels like it has changed as we emerge from the pandemic and set our sights beyond Covid-19. As the world has changed, our cultural institutions have had to rethink how they address the environmental, health and economic impacts, to ensure that they remain accessible to all in the future. At Purcell, they work with some of the nation’s most recognisable cultural institutions and have insights into how the sector can address these changes. At the Royal Society of Sculptors [RSS], they are undertaking conservation works to the listed building Dora House to improve its overall condition. The works will ensure the building befits its use and function in supporting sculptors throughout their careers and in facilitating a wider appreciation of sculpture via active engagement with the public.

Flexible design for a resilient economic business plan

Flexible designs help future proof the institution for inevitable changes in interpretative and exhibition media, curatorial practice, market, demand and user needs, such as at the RSS which hosts numerous events and has an ever-developing education and outreach programme. Flexible design limits the need for future physical changes and allows buildings to adapt quickly to changing demographics and new opportunities.

It can be a struggle to generate sufficient income from visitor charges alone and cultural buildings usually need revenue support generated from complementary but non-museum uses. For example, pre-Covid nearly 60% of the new Bristol Aerospace museum’s income came from commercial functions and events and at Cardigan Castle about 50% of its income comes from holiday lettings. Designs for cultural buildings need to look at similar alternative sources of revenue as part of a resilient business plan.

Intensify use to reduce environmental impact

Building in flexibility can also maximise space utilisation, with more intensive use increasing the efficiency in operation for reduced overall energy consumption. At the National Gallery, they converted spaces in the main building into a workspace for the organisation which facilitated the disposal of an adjacent building nearby; the energy consumption for running a consolidated workspace was reduced by around 75%.

Intensified use can also generate more income from individual spaces alone; there is not a great difference in the functional requirements of spaces used for conferences, meetings and learning which would allow a space to be used by more visitors from a wider market and for higher value uses. Similarly, planning a catering space with an adjacent multi-purpose space and/or an external terrace allows its seating provision to expand and contract relative to demand.

Intelligent design to reduce running costs

Intelligent design can assist the client in minimising operational staffing and hence costs, particularly where visitor/user numbers can fluctuate weekly or seasonally – for example, planning a reception area so that a single member of reception staff can also manage retail sales or invigilate a temporary gallery in quiet periods or combining retail and catering sales points with the same objective of reducing staffing levels in response to demand can have a significant impact on operating costs.